Ispirazione

Max Levy

In amber morning light I boarded a vaporetto and floated down Venice’s Grand Canal. Bit of a switch from Dallas.

Because Venice is a city without cars, I could hear the water lapping at the hull and at the stone foundations lining the waterways. We glided out into the Bacino, a vast jade lagoon that is the world’s most operatic setting of aquatic urbanism. Its shore is defined by the historic fabric, punctuated emphatically by works by Palladio and Longhena. Animating this scene were the slow-motion trajectories of gondolas, service craft, and suave mahogany water taxis. And presiding over it all was an enormous gold-leafed wind vane, surmounted by a figure of Fortune that has pivoted for centuries above the customs house.

Reaching the Arsenale, the medieval shipyards from which the Crusades were launched, I entered the slender gable end of a 16th century rope factory and walked its 1,000-foot length through a colonnade of 40-foot-tall cylindrical brick columns. Inside it and several other Arsenale buildings, and in the pavilions in the nearby Giardini (public gardens), were the exhibits of the 14th Venice Architecture Biennale. Somewhere in this lavish production I hoped to find some inspiration.

Rem Koolhaas was the curatorial ringmaster of this year’s Biennale. He established a three-part theme. In the rope factory was “Monditalia”, an attempt to combine Italian dance, music, theater, and film with architecture. These subjects were spatially shuffled and graphically rich, but much of the subject matter was so abstract as to be unfathomable. I had the impression of working my way through a giant Joseph Cornell box. While it is fascinating to regard Cornell’s mysteries from outside his sealed-box worlds, it is unsettling to be inside one.

“Absorbing Modernity” was the theme Koolhaas assigned to the 66 nations participating in this year’s Biennale. Many responded with illustrated histories of how modernism swept through. These were interesting, but the deluge of material presented was more fitting for books than for the flow of a huge exhibition. Some tried to solve this dilemma by editing down so much that all we were left with were a few ideas in white space. By contrast, several others threw out the theme, opting instead for exhibits that resembled the aftermath of a studio charrette.

Give Koolhaas credit for attempting to steer away from the traditional Biennale format of each nation offering up its architectural stars’ most spectacular stunts du jour. In doing so, he perhaps went too far in the other direction. With no star performances we were left mainly with displays of information. Despite the earnest efforts of at least 1,000 creative people from every part of the world, a hollow feeling prevailed.

I found myself filling the hollowness with exhibit details. In the American pavilion, for example, the custom trestle-table supports, fabricated from steel tubes, were admirable. In the Danish pavilion, delicate fiber-optic fittings had a magic about them in concert with the ephemeral objects they lit. A deep velvety charcoal stain on medium-density fiberboard was striking in the Arab Emirates display. White landscape contour models in the Canadian pavilion were enlivened with lines and motion by tiny digital projectors. Design incidents such as these were everywhere.

By far the most inspiring architecture and environmental design at the Biennale arose from the ancient Arsenale buildings themselves, from the arcadian setting of the Giardini, and from Sverre Fehn’s 1962 Nordic pavilion, one of the great modern buildings of the world.

The last curatorial component occupied the Giardini’s Central Pavilion. The exhibit presented Koolhaas’s research into the following list of subjects he deemed the “Elements of Architecture”: ceiling, wall, floor, façade, fireplace, corridor, balcony, toilet, ramp, stair, escalator, elevator, window, and door. The list was peculiar for its inclusions and exclusions. Indeed, a paradoxical atmosphere pervaded the entire pavilion. On the one hand, the subject matter was explored in a straightforward manner through vivid graphics and actual architectural fragments. On the other hand, the investigations were tinged with a surrealistic undercurrent. It was apparent that although Koolhaas did not display any of his own projects, we were walking through a three-dimensional rendition of his design process: a preamble of supposedly neutral research calculated to yield an off-beat, hip architectural story line.

Fatigued by the time I reached the ‘window’ section, I noticed a beckoning doorway. It opened out to a small courtyard enclosed by ivy-covered brick walls, with a lyrical shade structure, linear pools, and places to sit. Immediately on entering this space I felt restored, the hollowness filled. Every one of the “Elements of Architecture” missing from the 2014 Biennale was wordlessly restored in this outdoor room: space, light, and form; structure, material, and craft; alliance with nature; human repose. And then it suddenly dawned on me: the courtyard was designed by Carlo Scarpa . I had seen it in books over the years, a minor work, but I never knew where it was.

One of Scarpa’s masterworks is across town at the Fondazione Querini Stampalia, a 16th-century palazzo housing a library and art collection. Woven into its ground floor are a gallery and garden he designed in1959, profoundly Venetian in their embrace of water. The design acknowledges and takes pleasure in the aqua alta, the periods of high water that have troubled this city for a millennium. A fascinating composition of marble channels frames the floorplan of the gallery and garden, collects the high water, and slowly diverts it away.

By happy coincidence, the gallery exhibited Scarpa’s construction drawings for the work. Hand-drawn details at full scale showed every screw and deliberated dimension. Also on view was an exquisite little documentary film which captured an occasion of aqua alta inside the building: a sheet of water slowly moving across the marble floors, and tight detail shots of it overcoming the surface tension of stone. In the shadowed silence of these spaces one can sense something spiritual. Like Venice itself, this chapel-like gallery is balanced between timelessness and oblivion.

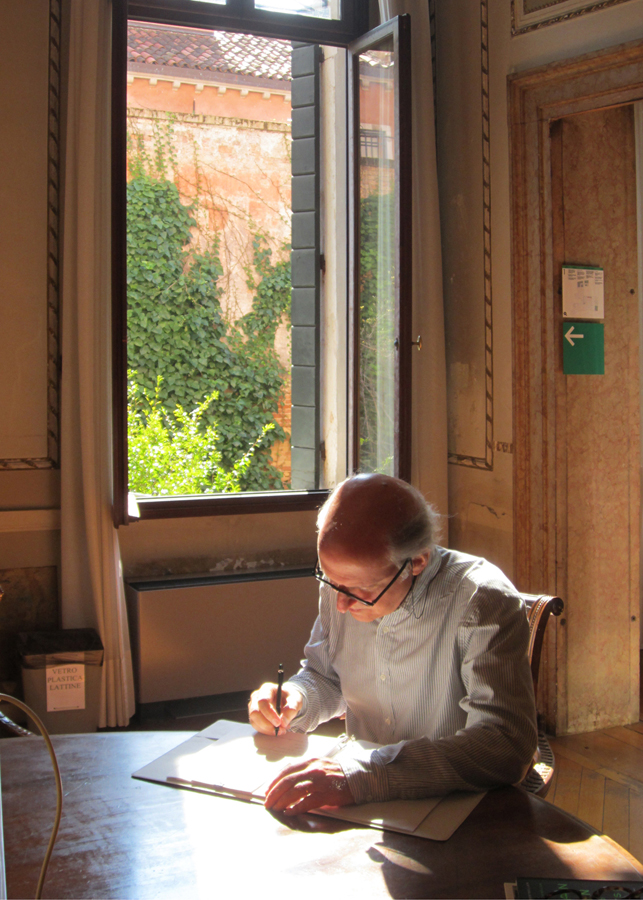

Upstairs, in the Querini library, I thought about how crucial inspiration is for architects. The world maddeningly resists what we strain to give it, and this wears us down. Fortunately, a little inspiration can redeem a lot of travail. I sat near an open window overlooking Scarpa’s garden, writing this article. The only sounds were the fountain below, distant church bells, and the library’s creaking wood floors. It was one of the most pleasurable afternoons of my architectural life.

Thoroughly enjoyed this good writing.

Long live Scarpa!!!